In order to avoid the antisemitism common in 1930s America, my father’s brothers all adopted Anglo-sounding last names—Coleman or Collins. My father Reuben was the only male sibling to keep his Jewish last name (Cohn, כֹּהֵן, meaning “priest” in Hebrew). My father explained to me how Jews of his generation had to mask their Jewish identities, or else they would be shut out of jobs and society. He kept his name and passed it down to me and my sister. We both kept it.

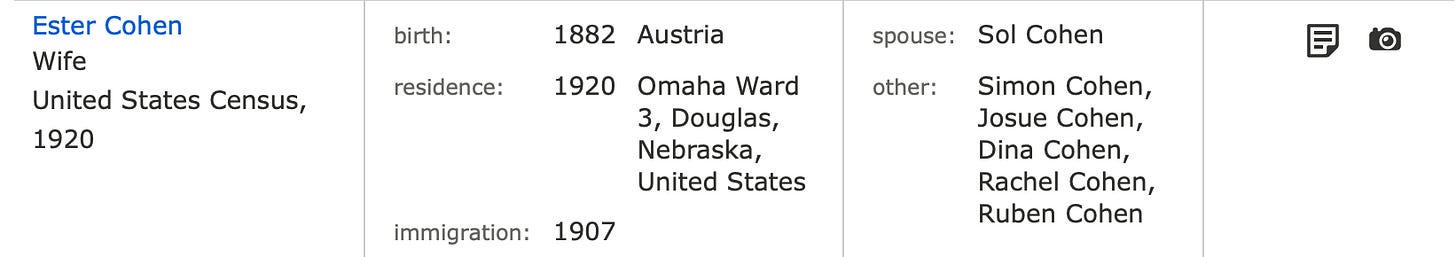

My fraternal grandparents immigrated from the Kingdom of Galicia, a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in 1907, near Krakow. Reuben’s eldest siblings were born in Europe, but my father was born in the United States. My father was sparing with details on why his parents moved to the United States—and I didn’t ask. My investigations into family genealogy uncovered answers as to when and where they moved, but not why.

The history of the region may hold family secrets. In the late 19th century, nationalist movements were rising. People wanted their governments to reflect their national characteristics—including the Polish people living under the auspices of Austria-Hungary, manifesting in the form of Narodowa Demokracja, a conservative political movement that employed antisemitic tactics to rally support for its vision of a Polish state. In 1898, riots in over 400 communities left homes and businesses looted, individuals injured. The Jews of Galicia had to leave for their own safety.

My father, Rube to his family and friends, was born in 1916 and grew up during the Great Depression. Two of his brothers joined the military, changing their names to avoid the widespread, informal barriers to fraternity and promotion within the armed forces. Rube, always known as a black sheep, took another path. Armed with the skills learned in his own father’s workshop, Rube specialized in locksmithing. Eventually he moved to Reno, Nevada—not exactly a diasporic oasis—where he ran his own small business and invented military-grade locks.

After two prior marriages—one an untimely death, the other a divorce—Rube married my mother in 1974. I was born a year later in 1975. Rube was a gregarious businessman, but a taciturn and private father. Although he retained a few cherished pieces of Judaica—a Hanukkah menorah, some Jewish and Yiddish books, and a few other tchotchkes—he kept his faith mostly to himself.

I understood my father was Jewish. His brothers and sisters were Jewish. When we traveled, my sister and I had to be reminded of customs while visiting a Jewish home. But I didn’t understand what it meant to be Jewish. Our family was not observant of any faith. I felt like there was no heritage to inherit.

On one hand, my mother was not Jewish, nor did she convert. From Rube’s perspective maybe this meant: why bother? However, it’s a terrible deprivation for me. Did he not realize I’d want to know my ancestry at some point? He did! Genealogy was briefly a passion project for him.

Why did he not share more of himself? More of his history? More of his faith? Was it to protect me from the bitterness of the antisemitism he faced as a young immigrant Jew in America? Did he believe that it was all in the past with the final nail driven with by the end of Nazi Germany? Or was he just not interested? Did he not think his goyishe children would care?

My father passed away in 2000. By the time I realized I had questions, it was too late to ask.

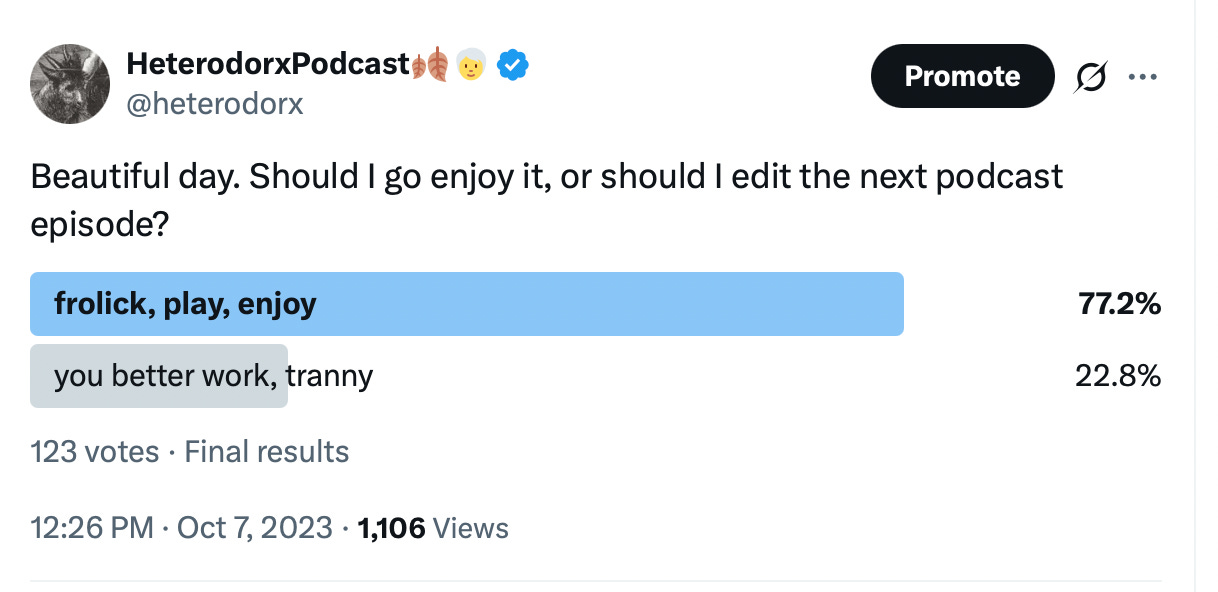

October 7, 2023, started as a promising day.

At the same time that fresh news was appearing of dead youth murdered at the Nova Music Festival, as images of bleeding women were being kidnapped and dragged back into Gaza, as videos of home security systems showed Hamas terrorists ruthlessly going from home to home murdering innocents.

While one new horror after another was becoming known, hundreds or maybe even thousands of people in America were celebrating. Within hours of the attack, Hamas-sympathizing anti-Israel activists had planned a large joint rally in celebration of the mass murder for the next day.

On October 8th, I called my sister. She wasn’t following the story. “We’re carrying Jewish last names,” I reminded her, “and there are many more people who hate Jews than we’ve realized. Please be careful.” I’m sorry to say that my warning was not an exaggeration. Since October 8th there have been anti-Israel rallies all over the United States. Worse, all over the world there has been a huge surge of violence directed at Jews outside of Israel.

On college campuses across the world—especially elite universities—students began rallying to praise the attacks. Groups like Student for Justice in Palestine, which distribute pro-Hamas propaganda, have ties to designated terrorist organizations such as Samiduon. Meanwhile, Chinese-owned TikTok allows modern blood libels to flourish in the form of viral videos, indoctrinating a generation of the gullible and bored into the world’s oldest hatred.

Not a day now passes without news of some unprovoked violence. A synagogue ransacked, its priceless Torah scrolls thrown to the floor. Jewish citizens of New York attacked by strangers. A Jewish girls’ school shot repeatedly. This is what it looks like when the demands to “globalize the intifada” are realized: attacks on innocent Jews. The frequency of these events appears to be increasing.

As we approach the two-year anniversary of the Hamas-led massacre, I see the pogroms my grandparents faced happening again in my lifetime.

My name is Cori Cohn, son of Reuben, and a descendant of those who carried the ark and lit the lamps. I did not inherit the rituals, but I feel the weight of my ancestry and the imperative to remember. I bear a Jewish name in a time when hatred of Jews is once again rising. Silence will not protect me. Nor will ignorance. I must speak. If not me, then who?

You favor your dashing father a fair bit!

Thank you for this powerful essay.

It’s true.

You are a Renaissance human and you are loved and respected by so many of us out here.